A Scene Unimaginable Five Centuries Ago

Inside the grandeur of the Sistine Chapel, under Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, King Charles III and Pope Leo XIV bowed their heads together in prayer, a moment unimaginable for nearly half a millennium.

For the latest news and updates, visit our website Restoring The Mind

It marked the first public joint prayer between a British monarch and the Pope since the English Reformation of the 16th century, when King Henry VIII broke from Rome and branded the papacy the enemy of Christian truth.

Cameras captured the British monarch, the Supreme Governor of the Church of England, standing beside the supreme pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church, not in opposition, but in devotion. For many observers, it was a picture of reconciliation between two faiths once locked in bitter hostility.

The Historical Chasm: The Reformation and the Birth of the Anglican Church

To understand the magnitude of this moment, we must revisit the centuries of conflict that divided these two faiths.

In 1534, King Henry VIII severed England’s ties with the Roman Catholic Church after Pope Clement VII refused to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. The move was not merely personal; it was a theological and political revolution.

The English Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, declaring the King the “Supreme Head on Earth of the Church of England.” In one stroke, papal authority in England was abolished. The Church of England was born a hybrid institution that retained many Catholic traditions while rejecting Rome’s authority.

For Catholics, this was schism; for Protestants, it was liberation.

And for both, it marked the beginning of centuries of religious warfare, persecution, and mutual condemnation.

The War of Words: When Anglicans Called the Pope the ‘Antichrist’

The rhetoric of the Reformation was savage.

Early Anglican theologians influenced by the writings of Martin Luther and John Calvin viewed the papacy as the embodiment of corruption and deception.

In the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion (1571), the Church of England codified this rejection of Rome:

“The Bishop of Rome hath no jurisdiction in this Realm of England.”

Article XIX went even further:

“As the Church of Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch have erred; so also the Church of Rome hath erred, not only in their living and manner of Ceremonies, but also in matters of Faith.”

Across sermons, pamphlets, and parliamentary acts, the Pope was routinely called “The Antichrist”, and the Roman Church the “Whore of Babylon.”

These weren’t mere insults; they were theological weapons.

To be a Catholic in Tudor or Stuart England was to be suspected of treason; loyalty to the Pope was considered disloyalty to the Crown.

By the time of Elizabeth I, England had executed priests, banned the Mass, and imposed heavy penalties on “recusants” who refused to attend Anglican services. The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 only deepened mistrust, reinforcing the idea that Catholicism was synonymous with conspiracy.

Thus, for centuries, the idea of an English king and a Pope praying together would have been unthinkable, even heretical.

Theological Divide: What Still Separates Rome and Canterbury

While both the Catholic Church and the Church of England trace their faith to the teachings of Christ and the early apostles, their doctrinal paths diverge sharply.

Here are some of the enduring differences that have defined the divide:

| Issue | Roman Catholic View | Anglican View |

| Authority | The Pope is the supreme head of the universal Church, with infallible authority when speaking ex cathedra. | The monarch is the Supreme Governor of the Church of England; the Archbishop of Canterbury is the spiritual head. No human is infallible. |

| Scripture & Tradition | Scripture and Church Tradition are equally authoritative under the Magisterium. | Scripture alone (Sola Scriptura) is the ultimate authority. |

| Sacraments | Seven sacraments (Baptism, Eucharist, Confirmation, Penance, Marriage, Holy Orders, Anointing of the Sick). | Two primary sacraments (Baptism and Eucharist), others treated as sacramental but not essential for salvation. |

| Priesthood | Only men can be ordained; priests must remain celibate. | Both men and women can be ordained; priests may marry. |

| Marriage & Divorce | Marriage is indissoluble; divorce and remarriage without annulment are not permitted. | Divorce is accepted; remarriage and same-sex unions are recognized in some provinces. |

| Mary and the Saints | Veneration of Mary and the saints as intercessors. | Reverence but no invocation; rejection of Marian dogmas like the Immaculate Conception. |

Anglican Hostility to Papal Power

The English Reformation was not just about religion; it was about power.

Henry VIII’s successors enshrined anti-papal sentiment in law and public life.

Catholics were excluded from public office, universities, and Parliament. The Test Acts of the 17th century forced officials to renounce the doctrine of transubstantiation, effectively banning Catholics from civil service.

For generations, Anglican sermons portrayed the Pope as a usurper of Christ’s authority. In some prayer books, believers were instructed to give thanks for deliverance “from the tyranny of the Bishop of Rome.”

By the 18th and 19th centuries, these hostilities had cooled politically but persisted culturally. Even as the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 lifted legal restrictions, suspicion remained.

When Pope Leo XIII declared Anglican holy orders “utterly null and void” in 1896 through his papal bull Apostolicae Curae, it reignited old wounds. Rome’s stance that Anglican priests and bishops were not validly ordained remains official Catholic doctrine to this day.

Queen Elizabeth II and the Era of Quiet Diplomacy

Fast-forward to the 20th century: the tone of hostility began to shift toward cautious respect.

Queen Elizabeth II, who reigned for 70 years, made history by meeting several Popes from John XXIII in 1961 to Francis in 2014. Though she remained steadfast in her Anglican faith, her visits symbolized reconciliation after centuries of alienation.

Her meeting with John Paul II in 1980 marked the first papal visit to Britain since before the Reformation. Later, she received him at Buckingham Palace in 2000 and, in 2010, welcomed Benedict XVI to the UK.

Yet even as relations warmed, the Church of England continued to move in directions that troubled Rome: the ordination of women (1994), the consecration of women bishops (2015), and, more recently, discussions on same-sex marriage.

These developments underscored that theological unity remained elusive, but the tone had changed from confrontation to conversation.

Enter King Charles III: A Monarch of Spiritual Curiosity

King Charles III cultivated a reputation as a spiritually eclectic monarch long before his accession. As Prince of Wales, he once said he would rather be known as “Defender of Faiths” than merely “Defender of the Faith.”

His worldview embraces dialogue with Islam, Judaism, and Christianity alike. As King, he has sought to redefine the monarchy’s religious role for a multicultural Britain.

That context makes his Vatican visit both logical and extraordinary: a public act of interfaith solidarity from a monarch who sits at the head of one of Rome’s oldest rivals.

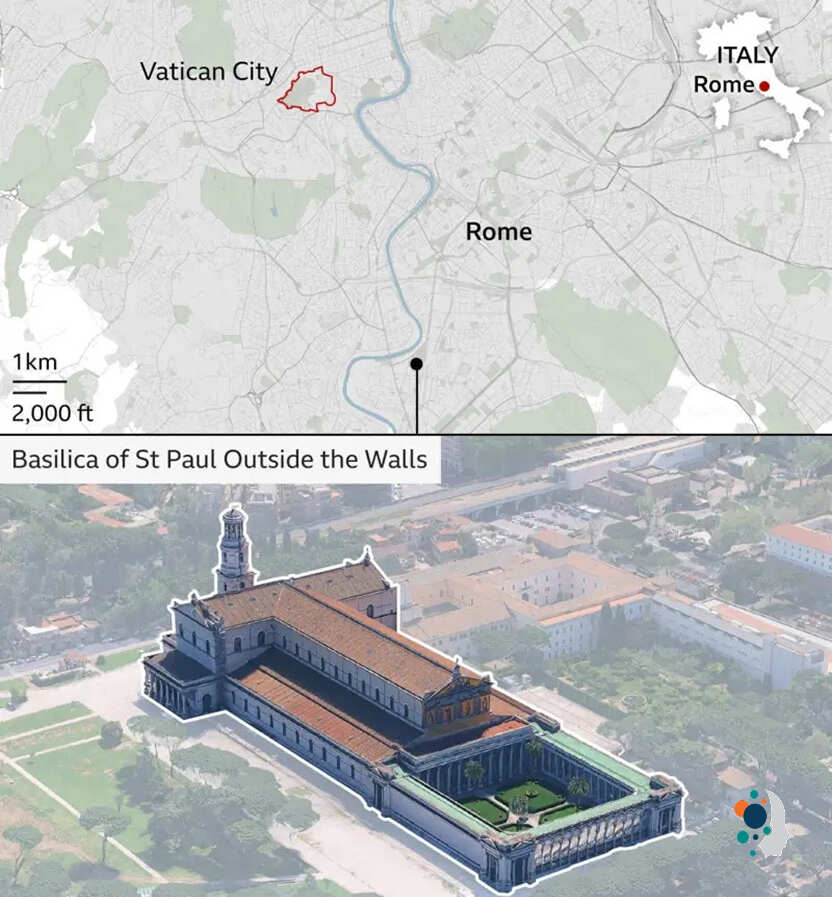

The Vatican Visit: A Moment of Sacred Optics

The visit began with regal pageantry.

A motorcade of royal vehicles entered St Peter’s Square. Swiss Guards stood to attention as King Charles and Queen Camilla were escorted to the Apostolic Palace for their meeting with Pope Leo XIV.

The two leaders exchanged symbolic gifts. The Pope presented an ancient illuminated manuscript from the Vatican archives; the King offered a hand-crafted silver cross inlaid with British oak.

Later, in the Sistine Chapel, they prayed side by side for peace, unity, and the protection of creation themes dear to both. The Pope’s emphasis on ecological responsibility echoed King Charles’ decades-long environmental advocacy.

The moment was not lost on historians. It was the first time in nearly 500 years that an English monarch and a Pope had publicly prayed together.

From Anathema to Alliance: The Shift in Religious Diplomacy

The image of Charles III kneeling beside the Pope represents more than polite diplomacy; it’s the visual undoing of centuries of theological vitriol.

To grasp its power, one must remember:

- In the 1500s, the Pope was branded “Antichrist.”

- In the 1600s, Catholic worship was criminalized in England.

- In the 1700s, Catholics were denied public rights.

- In the 1800s, the Vatican declared Anglican orders invalid.

- In the 1900s, dialogue began, but suspicion persisted.

- In 2025, the heads of both churches prayed together under one roof.

This progression tells a story not only of theology but also of civilization, how the same two institutions that once excommunicated each other can now unite in a prayer for peace.

Still Divided, Yet Drawn Together

Despite the warmth of the moment, neither side has altered its doctrines.

The Catholic Church continues to maintain papal supremacy and the centrality of Rome.

The Church of England continues to ordain women, bless same-sex unions, and affirm Scripture’s primacy over papal interpretation.

But through ecumenical bodies like the Anglican–Roman Catholic International Commission (ARCIC), both have found common ground on issues like social justice, ecology, and humanitarian aid.

As Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby said in a recent statement:

“We may not share one altar, but we share one mission to heal the world we inhabit.”

The Shadows Behind the Ceremony

While the Vatican prayer projected unity, Buckingham Palace faced controversy at home.

The Prince Andrew scandal, renewed by fresh allegations in a posthumous memoir by Virginia Giuffre, loomed over the royal narrative.

For critics, the Vatican trip also served as a strategic distraction, shifting the conversation from scandal to spirituality.

Royal analysts noted that the monarchy, struggling to maintain its moral image, benefits from the optics of religious diplomacy. Aligning the Crown with the Pope projects decency, continuity, and divine legitimacy qualities under strain in the age of tabloid scrutiny.

A Moment of Symbolism, Not Surrender

Some Anglican traditionalists worry that such gestures could blur confessional boundaries.

But palace officials insist that King Charles’ visit is symbolic, not theological, a gesture of goodwill, not a doctrinal shift.

Indeed, no joint statement on reunification was issued.

The Vatican described it as “a prayer for peace,” while Lambeth Palace framed it as “a moment of fellowship and shared responsibility.”

Still, in the eyes of millions, it was a miracle of diplomacy—the “Antichrist” and the monarch who once defied him now united in reverence.

Five Centuries in a Single Moment

| Century | Milestone |

| 16th | Henry VIII breaks from Rome; calls Pope “Antichrist.” |

| 17th | Catholics persecuted; Pope labeled “Whore of Babylon.” |

| 18th–19th | Catholic emancipation, but Anglican suspicion remains. |

| 20th | Queen Elizabeth meets multiple Popes; dialogue begins. |

| 21st | King Charles prays with Pope Leo XIV, a first since Reformation. |

Reactions from Around the World

The Vatican:

Cardinal Giovanni Parisi called the event “a moment of grace and healing, proof that the Holy Spirit can soften even 500-year-old hearts.”

The Church of England:

A statement from Archbishop Welby’s office hailed it as “a gesture of peace in an age that desperately needs reconciliation.”

Secular Critics:

Some accused both institutions of “performative diplomacy,” suggesting that the unity was more symbolic than substantive. Yet, as history shows, symbols have power sometimes greater than decrees.

An Age-Old Rift, a New Beginning

The story of England and Rome has been one of rupture and reconciliation, faith and politics, pride and penitence.

What began with Henry VIII’s defiance now finds a distant echo in Charles III’s prayer, not a surrender to Rome, but a recognition that faith, even fractured, can still unite.

Five centuries ago, the Pope was England’s enemy.

Today, he is the King’s ally in prayer.

Whether this moment becomes a turning point or a historical footnote, it stands as a reminder:

In religion, as in politics, time can turn adversaries into partners, even those once called Antichrist.